|

|

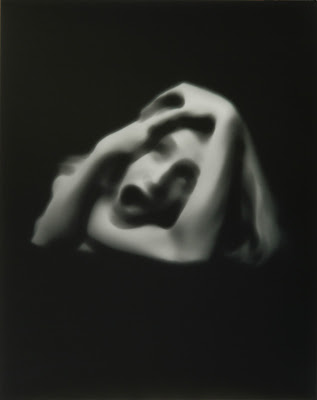

Robert Stivers, "O"#74," 2000.

Toned

gelatin silver print.

20 x16 in.

Gift of George Stephanopoulos,

Akron Art

Museum.

Courtesy of the Akron Art Museum

|

There is everything to absorb, fascinate and engage the visitor to the single gallery to Robert Stivers' Veiled Image at the Akron Art Museum. This photography show remains in place until mid-January, 2013. For Ohioans or western Pennsylvanians, this is good news, for the show is a loitering, contemplative one that can only ripen with multiple viewings. It gets under your skin and makes you wonder about your memory: Did you really see what you thought you did? What is the line between the personal emotion and recollected imagery Stivers evokes in his viewer, and what actually hangs there, printed on paper behind glass, protected by guards? In this "black and white" work with its broad palette of neutrals and grays, Stivers arranges remarkably plastic imagery. It reaches the depths of the mind before the eye can even focus on the content of the framed picture. The act of focusing only describes the content as a dictionary defines a word for a translator of poetry in a foreign language.

|

|

Installation view, Robert Stivers: Veiled Image, Akron Art Museum, July 28, 2012 through January 20, 2013.

Courtesy, Akron Art Museum.

|

|

|

Robert Stivers, FIC-Baby, 2000.

Toned gelatin silver print, 20 x 16 in.

Gift of Noemi and Daniel Mattis, Akron Art Museum.

Courtesy, Akron Art Museum

|

Veiled Image is an experience of forty individual photographs; of photographs the artist has purposefully clustered in groups; of photographs in a shadowed, story-telling room, where the story has a settled sequence, but no words. The story is what the viewer calls from personal recesses that Stivers' photographs stimulate by caress, innuendo, and fleeting pulses of electric current, all generated by his isolating composition. His subjects are human, natural, architectural, and interiors of rooms. But none of these is ever presented whole, nor is any presented entirely in focus. He distances the viewer from every shot, even (or especially) those that he brings us closest to by filling the frame. This technique is often used by photographers to make us feel that we can inspect the finest details of the pictured subject. Stivers strips away the illusion and reminds us that when we are very close, it can be impossible to focus. We respond to his work as consummate "art" photography, but in this, as in other techniques, he is in fact, realistic.

Each photograph is a highly composed tableau of great formal beauty. Each image is set like a jewel against a carefully toned background and, like the jewel, it is the only focal point within the frame. There is no competition for our attention; he gives us one event in each picture. Because of its singularity, the soft particularity of its arrangement, color, edge, and degrees of contrast each takes on great significance. When the picture is, as several are, grotesque, it can frighten us and send us scrambling for a context in which we can mute its impact.

|

|

Robert Stivers, Head with Open Mouth, from Series 5, 1995.

Gelatin silver print, 20 x 16."

Gift of George Stephanopoulos, Akron Art Museum.

Courtesy, Akron Art Museum.

|

This search for context ultimately drives the whole show. It's Stivers' device for turning us in upon ourselves, because the only context that we'll find is the one we create as we follow the numbered sequence of surprising images that leads us around the room.

An image like Head with Open Mouth is a fine example of the several levels of disorientation into which Stivers can draw us. What is the context of this image coming as it does late in the series, after the many others we have seen—figurative, architectural; ambiguous in threat, sexual content, placement in time or period?

But we're disoriented within the frame as well. Who—or even, what?—is depicted? Is he or she a contortionist? Are the limbs from one person or two? Is the expression the result of torture? Of song? Only our own fears and imaginations can determine the answers, or we must find the fortitude to accept not knowing.

Stivers is a self-taught photographer, a darkroom perfectionist who prints his work on matte papers. His academic training through a master's degree was in dance, which he practiced as dancer and choreographer into the 1980's when his career was ended by injury. After a stint in the business world (he became a stockbroker and insurance agent), he found a new creative home in photography, which he has pursued since 1988. His figurative photographs often depict himself or friends from the world of dance.

|

|

Palm Trees #1, from Series 8, 2002.

Gelatin silver print.

Gift of Mark Reichman, Akron Art Museum.

Courtesy,

Akron

Art Museum

|

Stivers' deep association with dance sensitizes me to another distinguishing aspect of all his work, with or without figures in it. While the show in general has the sense of being very still, in fact, every frame captures something in the middle of motion. At the simplest level, Stivers' love of soft-focus blurring can be interpreted as motion, as a transitional state on the way to precision. In the photo above, FIC-Baby, the cropped view isn't necessarily the end of a process: Since the image is unfocused, possibly the lens is still moving in, on the way to a visual goal we don't foresee it trying to reach.

In Palm Trees, #1, the movement of the trees is obvious: Not only the leaves, but the trunks have the stuttering appearance that time-exposure captures. We can not see the wind, but we can see its effects on the trees. Oddly, though, we don't see the effect of the wind on the clouds, which appear stationary by comparison with the twitching trees. In a brief time-exposure, this would be the case, but the effect is disconcerting. The subconscious accepts that we blend temporal units that awareness rigidly separates (e.g., duration, immediacy). In memory and in imagination, we barely make distinctions of time at all.

|

|

Wrapped Woman, One Eye, from Series 5, 1994.

Gelatin

silver print. 20 x 16 in.

Gift of James Bogin, Akron Art Museum.

Courtesy,

Akron Art Museum

|

I cannot pin down a particular cast of characters from among the faces we see in this show, but through the faces—some from sculpture or two-dimensional art, others from live models—we pass back and forth between historical periods; we are sometimes left between them, or in a zone freed of chronological placement all together. When we are left beyond clock time, we are given the power to locate the story somewhere other than Earth. Photos of women's faces illustrate this point, being figures we know and don't know, women we have seen, but whether in the flesh, in still art, cinema, or dreams it may be difficult to know. Whether we know them from Stivers' life or our own is, in itself, difficult to sort out.

|

Portrait of a Woman-R, from Series 5,

1997. Gelatin silver print. 20 x

16 in. Gift of James Bogin,

Akron Art Museum.

|

As dancers pirouette or leap across a stage,

we long to be able to stop their motion, just for an instant at

least, so we can linger in adoration over the powerful lines their bodies

draw, and can rejoice over the exquisite blend of fantasy and sweat.

If only we could hold them there, just for a moment.

Very often, good art tempts its audience

with desires to come closer, to inhabit or to possess the art they

see and admire. Sculpture galleries and galleries displaying material

culture in museums—furnishings, pottery, glass, jewelry—are all accented

with signs reminding visitors, "Do Not Touch!" because it is so

tempting to do just that.

Stivers' photographs are enticing that way. We want to

touch the photographs not as much as we want access to the deeply personal

secrets they hold. The artist's composition and techniques create a

veritable gingerbread house of temptations. We want to come so close that

we can reach through his illusions, to possess the secrets, the meanings;

to see through the haze, to focus through the blur, to apprehend what only by a

little bit eludes us. "I am so close," he makes us

feel. It's the feeling I have when I'm awakened by an alarm from an involved

and desperate dream, one that I'm certain is loaded with portent; in the moment

lost to the alarm, my hand would have moved through unfathomable time, into

certainty, and would have illuminated what success it was that I ached for in

my sleep.

|

Robert Stivers, Head in Mirror, 2002. Toned gelatin print,

20 x16 in. Gift of Noemi and Daniel Mattis, Akron Art Museum.

Courtesy, Akron Art Museum.

|

I want to put my hand through the mirror to affirm that the head is mine. Head in Mirror makes the distance clear and the foreground blurry, so it feels like reality is indeed beyond the mirror. That head is surely waiting for me; or it may very well be me. My eyes tell me that it is a block head; that it's a mannequin, carved from wood. But something makes me want to identify the beautiful, ornamental frame as my own vision. It's the love with which I see my resting self, the care and concern I have for that beloved, bald blockhead. Does this mirror reflect my heart? Predict my desire? Or project my vision into another state of mortal life?

|

|

Grouped photographs in

installation of Robert Stivers: Veiled Image at Akron Art

Museum, July 28, 2012 - January 20, 2013

|