Black and white are the colors of the Holocaust. The black and white starkness of documentary images result simply from the available technology of the 1940s. Respectful subdued tones follow suit as if to add color would be to pile unbearable sensation onto images and memories already overwhelming in color-drained grayscale.

So I was surprised when I walked into the gallery where Fabric of Survival: The Art of Esther Nisenthal Krinitz is showing at the Columbus Museum of Art until June 14. Filled with textiles detailing the memories of a Holocaust survivor, the room is alive with bucolic scenes of nature sewn from vari-colored fabric, crewel, and embroidery threads. Krinitz's hand-sewn tableaux feature Polish village life and landscape—backgrounds durable enough in memory to have survived all that the Nazis perpetrated; scenes in which the Nazis in fact seem dwarfed by the fields and forests around them.

These scenes of rivers, grain, and gardens remained vivid enough that when Krinitz began recording her childhood at age fifty, the horrors remained contained in images of a world much larger than the certainty of the death that only she and her sister, out of the whole family, escaped.

The tapestry above was the first she made, in 1978. She recollects her childhood home before the war. She and her brother swim in the river while their sisters look on. The villagers come and go about their tasks, and benign Nature dominates. Her house is big and solid, the size of a castle. It doesn't matter that Krinitz was fifty when she made this, for it is a picture of what the child still alive in her left behind.

This is the picture of home that is fundamental to personality and to character, the image that each of us harbors at some level. The top portion is linear and structured; the bottom is curvaceous and flowing. The whole is both stable and relaxed. The naive image has little artifice and an abundance of unfiltered, joyous expression.

During the 1970s, Krinitz originally made several pieces with subject matter like this, drawn from pre-war memories of Polish village life, where Jews and Gentiles lived side-by-side. She records memories of matzoh-making, of walking to holiday ceremonies on stilts that her brother made: The pleasure of simple, pre-industrial, pre-electrical, agricultural life ordered by the combination of seasonal and religious community observations.

After a long hiatus, Krinitz returned to her project in the 1990s, finally moving into the darkening story of her early adolescence and the arrival of the Nazis. Several of the Krinitz textiles show the indignities of Nazi sadism. She depicts soldiers cutting the beard off her grandfather; arousing the family in their nightclothes at gunpoint while neighbors gawked; marching Jewish boys off to forced labor where they were shot when depleted; and, finally, rounding up the Jews from among their neighbors for transport to death camps.

Esther and her thirteen year old sister fled (the rest of the family was killed). They survived by speaking only Polish and pretending they knew no German (closely related to their native Yiddish). They disguised themselves to find work for an elderly couple in a nearby village. In the scene above, Esther works in the garden that the old man to allowed her to plant. One day Nazis came and tried to question her. She explains in the embroidered caption:

"June 1943 in Grabowka. While I was tending the garden I had planted, two Nazi soldiers appeared and began to talk to me. I couldn't let them know that I understood them, so I just shook my head as they spoke. Dziadek, the old farmer who had taken me in as his housekeeper, came to stand watch near by, but the honey bees rescued me first, suddenly swarming around the soldiers. "Why aren't they stinging you?" the soldiers asked Dziadek as they ran out of the garden."

Take away the rifles, take away the caption, and what distinguishes these two scenes, made almost twenty years apart, first when the artist was 50 and then approaching 70?

The first, the pre-war memory, is quite specific—each of the five siblings is located, the house is recalled in loving detail—yet it is mythic too. It is an undatable memory of golden childhood. Esther's memory could be of life at four or fourteen. It is a recollection of well-being, innocence, stability, and love—a memory of place as feeling. Many adults recall such an idyll of childhood. But few recall the idyll's interruption by such sudden and complete trauma as Krinitz was to experience.

The pre-war scene is actually a tapestry. Every bit of the linen is covered with crewel embroidery so that the surface is entirely worked with stitches. Every inch of the surface has been touched and transformed by the artist's hand. The ideas of caressing and modeling come with this. It's not only a scene she recalls, but one she has invented as well—one she has caused to appear, and to appear just as she wants to remember it. She is its author.

The picture of her as an adolescent—no longer a girl, shoved into untimely adulthood—is not a tapestry. The sky, the "earth" of the garden and some other areas are simple fabric underpinning. The plants in the garden have been sewn in place by embroidery or appliqué; the bees, the flowers, the details of the figures, but the surface has not been as carefully stroked. In contrast to the first picture, it is entirely lined up. The importance of order at this stage in the girl's life was paramount. Even the bees on their hives rest in lines. Krinitz has made up this scene too. She has authored this scene not to refresh herself, but as a way to diffuse trauma.

More of the artist's time and attention have gone into a substantial narrative below the image the explains what might otherwise elude the viewer. She interprets the picture for us to be sure we know what she felt and how Nature continued to aid her.

The second image is remarkable for the way a survivor of great trauma pictures herself coping. The human figures—both the good and bad ones—remain small in the largely natural scene. She is located off to the side. She seems to mediate her own feelings of fear by spreading all possible feeling through the natural landscape, like healing wounds with resort to the earth. Even the bees, massing around the hives and buzzing around the soldiers, appear insignificant in the grand scheme of the picture. Krinitz controls her panic and fear by telling the story, controlling the context and perspective, and placing herself in a large framework.

"This was my family on the morning of October 15, 1942. We were ordered by the Gestapo to leave our homes by 10 a.m. to join all the other Jews on the road to Crasnik railroad station and then to their death."

This wall hanging, in narrative sequence previous to the one above, pictures Esther's recollection of the day her family had to face their impending deportation to the camps. This is a family portrait, undiluted by the presence of their killers. This was the day that Esther and her sister, in red, would flee.

Of the thirty-six pieces Krinitz made, this is one of the least dense in terms of sewing. The fabric background is largely plain cloth with a few large swathes of appliqué. Huge crows hunch on the housetop, symbols of impending death for the black-clad quintet.Two outsized sunflowers bloom for the escaping girls in their red capes.

Dark colors signify the grievous content of this picture but its momentous content is signaled by the size and forthright positioning of the family and the house. Nature does not soften or disguise emotion; if anything, it underscores the tragedy. Krinitz does not caress or decorate this image with thousands of strokes of her needle. In terms of presenting the most traumatic event of her life—a moment where she could be emotionally frozen forever—she is if brief, still heroically direct. In naive art, to place the figures near the bottom of the picture is to locate them in the most important place. It's to ground them, as children do in crayon drawings. This is the drawing that stays forever on the parents' wall, the treasured picture of the family, drawn by the daughter with a heart full of love. From this instant forward, Esther would be her own mother and her sister's. In her seventies, mother and child, she recounts the story of how this came to be.

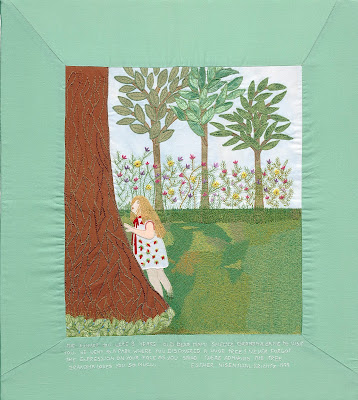

The final image in both the series and this show pictures a little girl who raises her arm to examine the trunk of a stout tree in a beautiful garden. The lawn, the bark, the flowers, the girl's hair—all are elaborately embroidered. They are touched all over with a loving, lingering hand. Krinitz has brought her story sequentially through the war years and her visit to the camp where her family was killed, a harrowing scene even in naif stitchery. She details and names the piles of ashes, the gas chambers, the burnt down home of the camp director. Aside from the girl's pigtails and dress, there is nothing bright in the meticulously catalogued scene.

In this final scene, she has lived a long life in Brooklyn with her husband whom she met in a refugee camp, with her daughters, and now celebrates her granddaughter, joyous in nature. There is an attempt at observational representation her; she has moved beyond the grip of memory and the burden of interpretation into a real and safe present. The girl is little and the tree next to her is really enormous; there is actual scale and it feels reassuring. The border is green, the text is white: "When you were three years old dear Mami Sheine, Grandma came to visit you. We went to a park where you discovered a huge tree. I never forgot the expression on your face as you stood there admiring the tree. Grandma loves you so much."

Grandma is free and insures that she will be part of another little girl's strength, no matter what comes.

|

| Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Swimming in the River, 1978. Embroidery on linen. Art and Remembrance. |

These scenes of rivers, grain, and gardens remained vivid enough that when Krinitz began recording her childhood at age fifty, the horrors remained contained in images of a world much larger than the certainty of the death that only she and her sister, out of the whole family, escaped.

The tapestry above was the first she made, in 1978. She recollects her childhood home before the war. She and her brother swim in the river while their sisters look on. The villagers come and go about their tasks, and benign Nature dominates. Her house is big and solid, the size of a castle. It doesn't matter that Krinitz was fifty when she made this, for it is a picture of what the child still alive in her left behind.

This is the picture of home that is fundamental to personality and to character, the image that each of us harbors at some level. The top portion is linear and structured; the bottom is curvaceous and flowing. The whole is both stable and relaxed. The naive image has little artifice and an abundance of unfiltered, joyous expression.

During the 1970s, Krinitz originally made several pieces with subject matter like this, drawn from pre-war memories of Polish village life, where Jews and Gentiles lived side-by-side. She records memories of matzoh-making, of walking to holiday ceremonies on stilts that her brother made: The pleasure of simple, pre-industrial, pre-electrical, agricultural life ordered by the combination of seasonal and religious community observations.

|

| Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, The Bees Save Me, 1996. Art and Remembrance. |

Esther and her thirteen year old sister fled (the rest of the family was killed). They survived by speaking only Polish and pretending they knew no German (closely related to their native Yiddish). They disguised themselves to find work for an elderly couple in a nearby village. In the scene above, Esther works in the garden that the old man to allowed her to plant. One day Nazis came and tried to question her. She explains in the embroidered caption:

"June 1943 in Grabowka. While I was tending the garden I had planted, two Nazi soldiers appeared and began to talk to me. I couldn't let them know that I understood them, so I just shook my head as they spoke. Dziadek, the old farmer who had taken me in as his housekeeper, came to stand watch near by, but the honey bees rescued me first, suddenly swarming around the soldiers. "Why aren't they stinging you?" the soldiers asked Dziadek as they ran out of the garden."

Take away the rifles, take away the caption, and what distinguishes these two scenes, made almost twenty years apart, first when the artist was 50 and then approaching 70?

The first, the pre-war memory, is quite specific—each of the five siblings is located, the house is recalled in loving detail—yet it is mythic too. It is an undatable memory of golden childhood. Esther's memory could be of life at four or fourteen. It is a recollection of well-being, innocence, stability, and love—a memory of place as feeling. Many adults recall such an idyll of childhood. But few recall the idyll's interruption by such sudden and complete trauma as Krinitz was to experience.

The pre-war scene is actually a tapestry. Every bit of the linen is covered with crewel embroidery so that the surface is entirely worked with stitches. Every inch of the surface has been touched and transformed by the artist's hand. The ideas of caressing and modeling come with this. It's not only a scene she recalls, but one she has invented as well—one she has caused to appear, and to appear just as she wants to remember it. She is its author.

The picture of her as an adolescent—no longer a girl, shoved into untimely adulthood—is not a tapestry. The sky, the "earth" of the garden and some other areas are simple fabric underpinning. The plants in the garden have been sewn in place by embroidery or appliqué; the bees, the flowers, the details of the figures, but the surface has not been as carefully stroked. In contrast to the first picture, it is entirely lined up. The importance of order at this stage in the girl's life was paramount. Even the bees on their hives rest in lines. Krinitz has made up this scene too. She has authored this scene not to refresh herself, but as a way to diffuse trauma.

More of the artist's time and attention have gone into a substantial narrative below the image the explains what might otherwise elude the viewer. She interprets the picture for us to be sure we know what she felt and how Nature continued to aid her.

The second image is remarkable for the way a survivor of great trauma pictures herself coping. The human figures—both the good and bad ones—remain small in the largely natural scene. She is located off to the side. She seems to mediate her own feelings of fear by spreading all possible feeling through the natural landscape, like healing wounds with resort to the earth. Even the bees, massing around the hives and buzzing around the soldiers, appear insignificant in the grand scheme of the picture. Krinitz controls her panic and fear by telling the story, controlling the context and perspective, and placing herself in a large framework.

|

| Esther Nisehnthal Krinitz, Ordered to Leave Our Homes, 1993. Embroidery and fabric collage. Art and Remembrance. |

This wall hanging, in narrative sequence previous to the one above, pictures Esther's recollection of the day her family had to face their impending deportation to the camps. This is a family portrait, undiluted by the presence of their killers. This was the day that Esther and her sister, in red, would flee.

Of the thirty-six pieces Krinitz made, this is one of the least dense in terms of sewing. The fabric background is largely plain cloth with a few large swathes of appliqué. Huge crows hunch on the housetop, symbols of impending death for the black-clad quintet.Two outsized sunflowers bloom for the escaping girls in their red capes.

Dark colors signify the grievous content of this picture but its momentous content is signaled by the size and forthright positioning of the family and the house. Nature does not soften or disguise emotion; if anything, it underscores the tragedy. Krinitz does not caress or decorate this image with thousands of strokes of her needle. In terms of presenting the most traumatic event of her life—a moment where she could be emotionally frozen forever—she is if brief, still heroically direct. In naive art, to place the figures near the bottom of the picture is to locate them in the most important place. It's to ground them, as children do in crayon drawings. This is the drawing that stays forever on the parents' wall, the treasured picture of the family, drawn by the daughter with a heart full of love. From this instant forward, Esther would be her own mother and her sister's. In her seventies, mother and child, she recounts the story of how this came to be.

|

| Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Granddaughter, 1999. Embroidery and fabric collage. Art and Remembrance. |

The final image in both the series and this show pictures a little girl who raises her arm to examine the trunk of a stout tree in a beautiful garden. The lawn, the bark, the flowers, the girl's hair—all are elaborately embroidered. They are touched all over with a loving, lingering hand. Krinitz has brought her story sequentially through the war years and her visit to the camp where her family was killed, a harrowing scene even in naif stitchery. She details and names the piles of ashes, the gas chambers, the burnt down home of the camp director. Aside from the girl's pigtails and dress, there is nothing bright in the meticulously catalogued scene.

In this final scene, she has lived a long life in Brooklyn with her husband whom she met in a refugee camp, with her daughters, and now celebrates her granddaughter, joyous in nature. There is an attempt at observational representation her; she has moved beyond the grip of memory and the burden of interpretation into a real and safe present. The girl is little and the tree next to her is really enormous; there is actual scale and it feels reassuring. The border is green, the text is white: "When you were three years old dear Mami Sheine, Grandma came to visit you. We went to a park where you discovered a huge tree. I never forgot the expression on your face as you stood there admiring the tree. Grandma loves you so much."

Grandma is free and insures that she will be part of another little girl's strength, no matter what comes.