| |

|

Each of Opie's sitters appears before a background of profound, impenetrable black. Whether we register that as a blankness or as infinite depth, the effect is in either case the same. It places the subject in a timeless three-dimensional space entirely his or her own, unrelated to any other place or moment.

The effect is to sculpt the figure out of this medium of black. The light not only defines the subject's features, emphasizing some over others, but frees the form from the darkness as sculptures are said to free figures from great pieces of stone. So, through two galleries of portraits, each figure is captured at a second birth, born not of flesh, but of mind, effort, and imagination These are individuals sprung like Athena from Zeus's head, fully grown and mature. ( An interesting comparison can be made at http://www.modigliani-drawings.com/nude%20in%20profile.htm .)

In her portrait, Miranda wears a gown of almost Quakerish simplicity and understatement. Its claret color and her red hair mediate between blackness and the luminous skin and blue eyes that shine from her steady, resolute expression. Beauty can be a poisoned gift. Here, beauty is neither disguised nor avoided; its possessor can carry the weight with chin slightly lifted, directly returning the viewer's gaze. The image portrays the strength, stature, and balance of a flawlessly beautiful woman with nothing—not even her perfect face—to hide.

Miranda, a three-quarter standing portrait of a woman of noble bearing, is clearly related to a long tradition of Western portraiture, evident in any museum one cares to visit. While this particular woman captivates us with her seriousness and beauty, we also know that, individual, her photographer places her among a class of persons demanding our highest respect. The setting, the attention to details, the lighting all tell us so. Do we really need to know who she is? Here is a distinguished individual who is also a participant in the centuries-old tradition of women posed for posterity. She is one; she is another one.

When we visit museum galleries hung with grand and stirring portraits of Renaissance, Enlightenment, or nineteenth century royalty, clergy, poets, and concubines, how often do we know who those portrayed persons were, or what they accomplished in the world? Certainly not as often as we'd like. King George? Henry? And what number? Not a clue! Yet we interpret the images through our understanding, general knowledge, and imaginations via the art itself, through conventions and deviations from them; from our own reactions to images of luxury, eccentricity, and beauty. We react to the story the artist has told and we create the central figure to satisfy our use of the painting. Ahistorical? Anachronistic? Yes. Utterly commonplace? Yes again.

In fact, we do the same thing with contemporary portraits simply because we don't know everyone who is thought to be important to image-makers. Nor are we supposed to. In this series of portraits, Opie identifies her subjects by first names only. How they were posed appears to have been largely up to the artist, who received lovely testimonials from many of her subjects for the generous or enlightening experiences they had with her. As recounted in gallery notes, the artist Kara Walker remarked that before many scheduled portrait sessions, she has been less than at her best: "There are a handful of images by well-known artists out there of me at my darkest, lowest points. Cathy's manner and the resultant images show me feeling cool, collected, showing my muscles…I felt a rush of ownership or at least fellowship—that we were going to endeavor to correct this past."

|

|

Catherine Opie, Mary, 2013. Pigment print, 50 x 38.4. ©Catherine Opie. Image courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

|

So, yes, Opie's subjects are eminent people, contemporary artists working in the avant garde of visual arts, literature, performance, and music. Even though many will be recognized by a relatively small audience, they are nonetheless constantly imaged. Miranda, above, is the filmmaker/performance artist/writer/actor Miranda July. If you haven't seen her before, just Google for her image: There are pages of them. It's a worthwhile exercise in understanding the difference between a picture and a portrait.

In the present day, pictures are everywhere by accident and by design. The tradition of grand portraits in which Opie places this series derives from times in which images of the great were rare and precious. A painted portrait of Voltaire would become the basis for engravings, which could be printed and disseminated at low cost. But the world was not saturated by an infinite flow of unique images of a single eminent person who was redecorated and whose personality was recast daily. There was a constancy about the central identities of intellectuals and artists.These portraits, in this form, reclaim that idea of constancy.

To the extent that Opie's portraits help define and settle identities, she uses visual tradition as a structure upon which she arranges the ideas, works, and core identities of the individuals portrayed. The black background, the exquisitely controlled lighting, the dignity of the posing, the shapes of the portraits: These form the traditional framework that assure a place of honor. Within that framework, the individual is exactly as portrayed—nude or clothed; regal or workmanly; facing forward or back to us; looking into the distance, or daring us to return a gimlet gaze.

|

Catherine Opie, Idexa, 2012. Pigment print, 50 x 38.4. ©Catherine Opie. Image courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

|

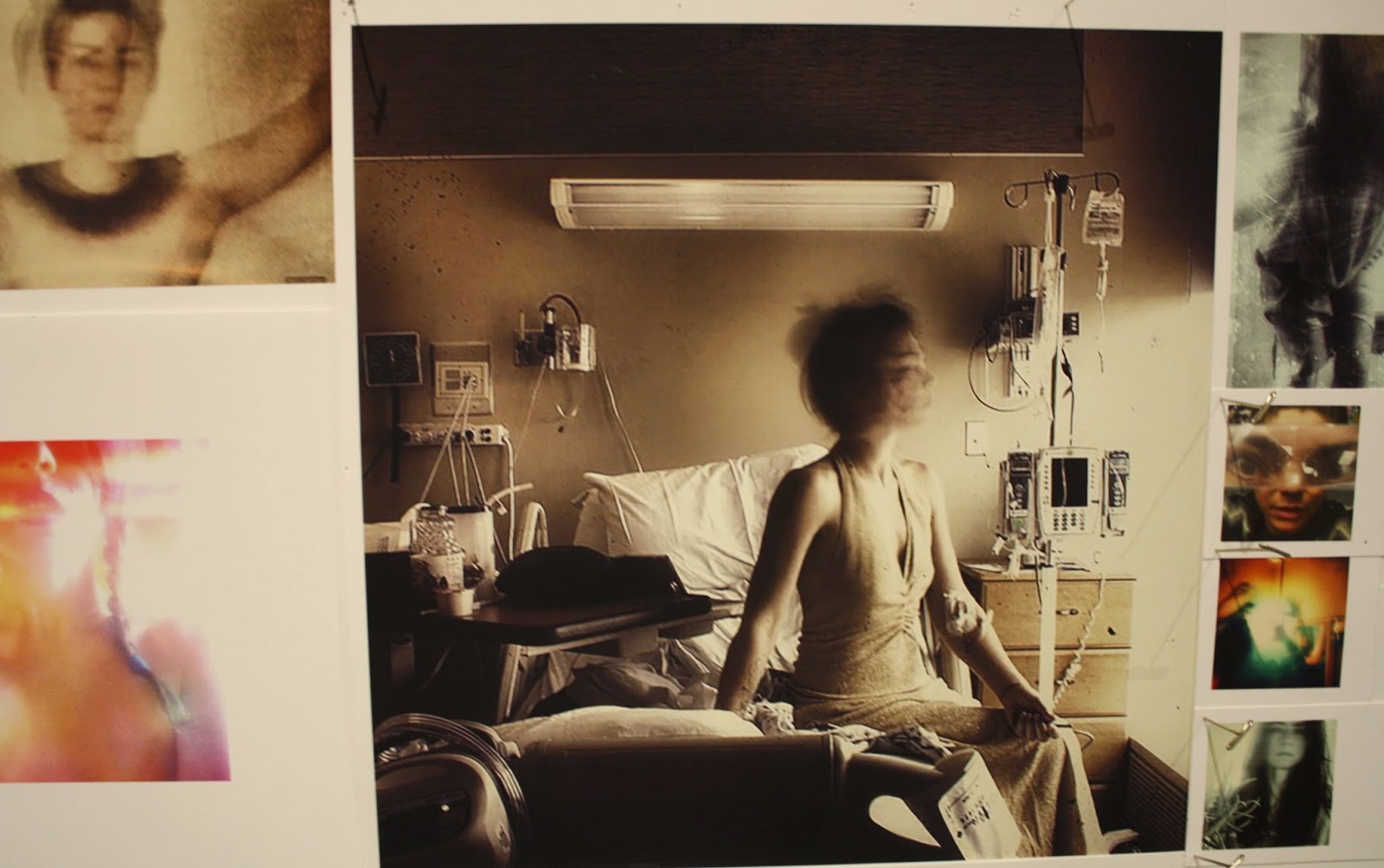

While Miranda's classicism provides studied definition to a woman whose image is ubiquitous and casually broadcast, in Mary and Idexa, Opie uses conventions to bring the temperature of uncommon images down. Tradition soothes expectations and we are eased into accepting the differences in purpose and outlook revealed in these portraits. Formality does not stifle outrage, but it is a leveler; it brings discussion back to a home base.The women depicted here are not women with traditional self-awareness or lives. But who they are and who they wish to reveal are who we will see in the same dignified ways we would see queens and saints and famous lovers portrayed.

These two portraits will hang comfortably in haughty halls centuries hence, among the late Maries and Georges and Voltaires; the images will command respect beyond our period and, like all historical images, will require the acts of research and imagination that we are asked to give to the past from our own present. The question cries out: Can we understand the genius of difference in our own time with the acceptance we grant to heroes of the past? Can we imaginatively condense the years it takes gradually to achieve understanding through the mediation of formal visual traditions?

|

|

The Portraits in Opie's show are so intense, so detailed and personal that the curator, Bill Horrigan, made the interesting decision to divide the portraits into groups of three or four separated with single, large scale landscapes the artist's. Some of these, like the one above, I am sorry to feel obliged to call a landscape, as I think it is so very open to—so inviting of—free interpretation. But their use is fascinating, contrasting as they do with the entirely unfocused with portraits in which every detail is in sharp focus. Neither is realistic, of course. But the effort the portraits compel from the viewer, with a degree of focus that only incites us to come ever closer—sends one into the landscapes as if suddenly lifted out of stress and sent into cool reverie. It is both relaxing and disorienting, for there is no middle between the two photographic approaches. I like this arrangement better in the first floor gallery, which is larger than the narrow upstairs room. With lots of room to stand back and to take in a whole long wall, the effect of the combination is lovely and its meaning is clear. The closer one is to the works, upstairs, the harder the effectiveness of the contrast is to grasp.

If there is any problem with this show, it's that any single work in it could stand alone as a show in itself. It's an embarrassment of riches to be sure. The portraits are of a size and degree of detail that each is a map of the world, a voyage out far beyond anything you can notice at the outset. Every well-crafted detail is surrounded by a field of more and more subtle and revealing manipulations of Opie's medium. They are captivating and fulfilling—and absurd to present in miniature, in a blog. Don't miss a chance to see them.

If there is any problem with this show, it's that any single work in it could stand alone as a show in itself. It's an embarrassment of riches to be sure. The portraits are of a size and degree of detail that each is a map of the world, a voyage out far beyond anything you can notice at the outset. Every well-crafted detail is surrounded by a field of more and more subtle and revealing manipulations of Opie's medium. They are captivating and fulfilling—and absurd to present in miniature, in a blog. Don't miss a chance to see them.|

Catherine Opie, Hamza, 2013. Pigment print, 33 x 25 in.

©Catherine Opie, image courtesy the artist and Regen Projects,

Los Angeles

|