How lovely to have a backyard pond like Betsy Furlong DeFusco does, with time to contemplate its inspiration on canvas, in color. "It's very relaxing to sit and watch the fish swimming around endlessly in a swirl of color, and I soon became engaged in seeing a whole world of activity in a tiny body of water. I am constantly inspired by the different worlds in nature and by the act of painting itself as I explore the edge between abstraction and representation," she tells us in the statement she prepared for her large exhibition, which hangs at the Ohio State University Faculty Club through October 28.

While DeFusco's work begins with observation, her interest in invented color moves the paintings toward abstraction, as do her simplification of forms and her evident interest in the decorative. This show is genuinely delicious. It is restful, peaceful, alluring. The floating forms of water lily pads with goldfish idling among them soothe as much painted in intense pastels as would their real—and less vivid—originals. Her strong colors, softened by applied layers of transparent glazes, read at a distance as water color rather than oil because they are sheer and give the illusion of translucent overlap. Seasnake Sushi 2 is such a work, an expression of exuberance created by color, shape, line, and the artist's ability to use them as she will.

Any painter who chooses water lilies and a pastel palette to work in is bound to be compared to Monet; DeFusco is wide open to this comparison, with her luscious colors and dreamy, floating forms. It's wise to remember, though, that Monet's mission was entirely different: He was a student of light, intent on rendering reality in a new way, working to represent.

I'm not so sure that this is DeFusco's mission, however beguiling her palette. While in Floating Colors we can imagine blue water giving over to green, or the play of shadows on water having this color effect, the lack of detail in the lily pads tells us that the artist is not out to convince us about the nature of what she saw. What she "captured" was a vision, in which a scene of lily pads on water was an inspiration for a foray into color, her emotional and imaginative center. Another basic thing to notice is DeFusco's evenhanded brushwork. In Floating Colors, as in many of the pieces in this show, the strong strokes back and forth show no impulse to mimic nature. They shuttle across the scene to form a scrim and to create an impossible simultaneous motion suggested by the cuts in the leaves: Some move to the left, others to the right, all on the same current. (If you inspect images on her Facebook page, linked above, you can get a better sense of these surfaces.)

In DeFusco's series of small-scale lily pad paintings, a favorite of mine is Near the Shore.

The forms in this work fill the picture plane in sizes and more complicated relation than in some, suggesting a possible reality for the leaves. At the same time, the edges of the forms are indistinct and, compared to most of the work in the show, the colors are very muted; I feel that I have to rub something from my eyes to get close enough to the picture.

I think that DeFusco has hit a particular sweet spot here, between painting a scene and painting a dream. The strong horizontal brush strokes that span the surface of the painting once again lend a quiet dynamic to what appears to be a cool and settled scene.

Two more small paintings won my heart, two that read as realistic. Swimming Through features a sturdy gold fish, not abstract at all, swimming in clear water just below a few small lily pads. The water is gray-blue. The plants are green. The fish is gold. All the elements are painted with sufficient detail to convey a sense of their reality.

I like the point of view. I like it that we are situated so that we are looking absolutely straight down at this fish. I can't quite imagine how I got here—so close and so directly above—without disturbing the quiet calm of the scene. I feel like I'm in a privileged place. It's special, but it's not abstract. What's even more special is that it is obviously fleeting. While there is a lot of implied movement in DeFusco's work, this is both a fish and the fish. It's not one of a mass of moving forms. We know which way it's going, and that it will soon be gone. There's a drama in this fleeting scene that the more lively and crwded paintings cannot have.

I also enjoy the muted colors of the painting, especially in contrast to those around it. DeFusco loves the pinks and bright tropical colors, so her show is quite a brilliant experience. That Swimming Through feels like something self-sufficient and happy in its calm literal expression is especially refreshing in context.

Autumn Pond shares with Swimming Through this nod toward literal reality. Both paintings move into a contemplative space as a result, a space that the more colorfully abstract paintings don't occupy. The distance between this and Seasnake Sushi 2 is vast.

The focus of this painting is very clear; the subject is the yellow lilly pad trailing a tendril that disappears out of the bottom left corner. There is a distinctly dynamic aspect to the composition. Even though it is not a swift or driving picture, there is a sense of something to come that adds purpose and story. The yellow form crosses a background line, moving from gray-blue water into water clear enough to reflect foliage in all its true, deep and brooding green color. A flat, stucco pink leaf intrudes at the top margin from DeFusco's abstract and artificial world.

I'm happy to accept this embassy from the other side. It's beautiful and it reminds me of the edge that DeFusco works. But it doesn't undo this lovely moment of reality, when a resting leaf floats between two worlds, becalmed between the aesthetic of color combinations and the truth of incipient decay.

If DeFusco's show has any major flaw, it's that there is too much work in it. She has produced a prodigious body of paintings on a few subjects in a special, tight pallet. I think she would be better served by withholding some and piquing the appetite for more. But beautiful it is. For the art lover who watches the leaves change with a sense of regret, this is the show to see to cling to the sweetness of warm days and long, slow, contemplative days of ripe beauty.

|

| Betsy DeFusco, Seasnake Sushi 2. Oil on wood panel, 9 x 12." (Leafy vines decorate the fish shapes like strings of festive lights draped from a balcony at an oceanside resort.) |

|

| Betsy DeFusco, Floating Colors 2. Oil on wood panel, 16-3/4 x 21-3/4." |

I'm not so sure that this is DeFusco's mission, however beguiling her palette. While in Floating Colors we can imagine blue water giving over to green, or the play of shadows on water having this color effect, the lack of detail in the lily pads tells us that the artist is not out to convince us about the nature of what she saw. What she "captured" was a vision, in which a scene of lily pads on water was an inspiration for a foray into color, her emotional and imaginative center. Another basic thing to notice is DeFusco's evenhanded brushwork. In Floating Colors, as in many of the pieces in this show, the strong strokes back and forth show no impulse to mimic nature. They shuttle across the scene to form a scrim and to create an impossible simultaneous motion suggested by the cuts in the leaves: Some move to the left, others to the right, all on the same current. (If you inspect images on her Facebook page, linked above, you can get a better sense of these surfaces.)

In DeFusco's series of small-scale lily pad paintings, a favorite of mine is Near the Shore.

|

| Betsy DeFusco, Near the Shore. Oil on wood panel, 16-3/4 x 21-3/4." |

The forms in this work fill the picture plane in sizes and more complicated relation than in some, suggesting a possible reality for the leaves. At the same time, the edges of the forms are indistinct and, compared to most of the work in the show, the colors are very muted; I feel that I have to rub something from my eyes to get close enough to the picture.

I think that DeFusco has hit a particular sweet spot here, between painting a scene and painting a dream. The strong horizontal brush strokes that span the surface of the painting once again lend a quiet dynamic to what appears to be a cool and settled scene.

|

| Betsy DeFusco, Swimming Through. Oil on wood panel. 12 x 12." |

I like the point of view. I like it that we are situated so that we are looking absolutely straight down at this fish. I can't quite imagine how I got here—so close and so directly above—without disturbing the quiet calm of the scene. I feel like I'm in a privileged place. It's special, but it's not abstract. What's even more special is that it is obviously fleeting. While there is a lot of implied movement in DeFusco's work, this is both a fish and the fish. It's not one of a mass of moving forms. We know which way it's going, and that it will soon be gone. There's a drama in this fleeting scene that the more lively and crwded paintings cannot have.

I also enjoy the muted colors of the painting, especially in contrast to those around it. DeFusco loves the pinks and bright tropical colors, so her show is quite a brilliant experience. That Swimming Through feels like something self-sufficient and happy in its calm literal expression is especially refreshing in context.

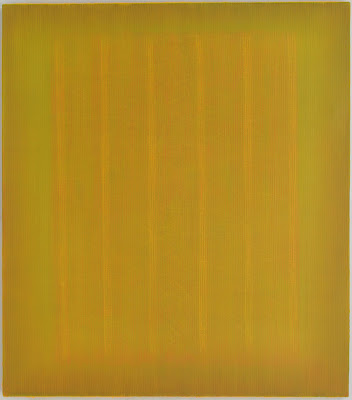

Autumn Pond shares with Swimming Through this nod toward literal reality. Both paintings move into a contemplative space as a result, a space that the more colorfully abstract paintings don't occupy. The distance between this and Seasnake Sushi 2 is vast.

|

| Betsy DeFusco, Autumn Pond. Oil on wood panel, 12 x 12." |

The focus of this painting is very clear; the subject is the yellow lilly pad trailing a tendril that disappears out of the bottom left corner. There is a distinctly dynamic aspect to the composition. Even though it is not a swift or driving picture, there is a sense of something to come that adds purpose and story. The yellow form crosses a background line, moving from gray-blue water into water clear enough to reflect foliage in all its true, deep and brooding green color. A flat, stucco pink leaf intrudes at the top margin from DeFusco's abstract and artificial world.

I'm happy to accept this embassy from the other side. It's beautiful and it reminds me of the edge that DeFusco works. But it doesn't undo this lovely moment of reality, when a resting leaf floats between two worlds, becalmed between the aesthetic of color combinations and the truth of incipient decay.

If DeFusco's show has any major flaw, it's that there is too much work in it. She has produced a prodigious body of paintings on a few subjects in a special, tight pallet. I think she would be better served by withholding some and piquing the appetite for more. But beautiful it is. For the art lover who watches the leaves change with a sense of regret, this is the show to see to cling to the sweetness of warm days and long, slow, contemplative days of ripe beauty.