|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

|

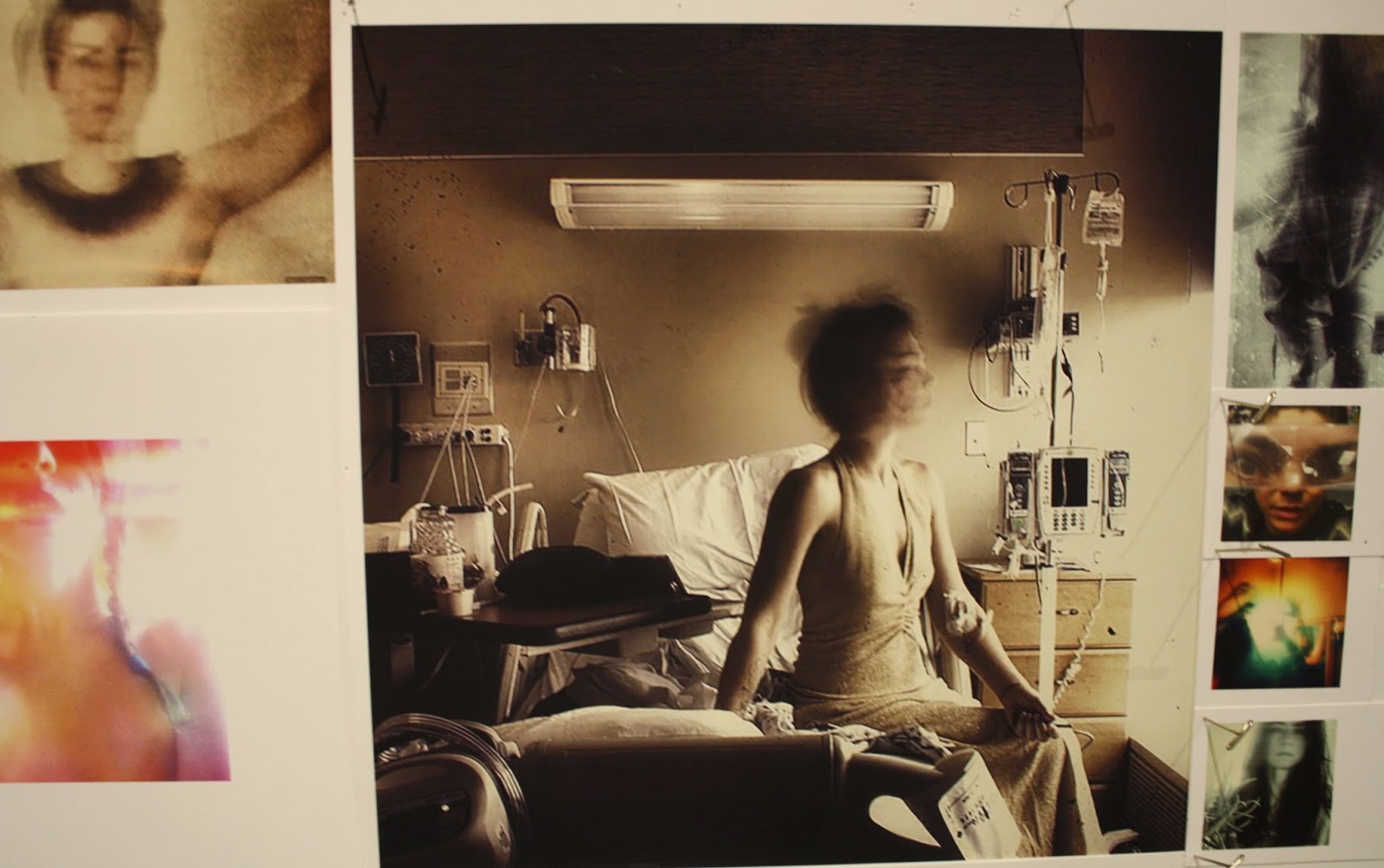

| View of gallery wall in Maika Carter's Call It Something or Call It Nothing |

chapters of a photographic narrative. Its progression from subject to subject is clearly delineated; the content of each unit is presented in distinct, striking images, and the movement from section to section feels organic. Best of all, the last chapter constitutes a synthesis up of all that has come before. What has it added up to? Something essential and true packed into the the mundane and happenstance? Or an affirmation of meaning in life's trivial accumulation?

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. Group photo including the artist. |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

But the next section of colorful photographs moves us in the way we respond to the scrapbook of a big, happy family. Carter brings us to a large, rambling spread of smiling relatives and friends of several generations—people happy to be together, happy to do what they are doing, feeling special and loved. I feel certain that this passage of the exhibition will leave no viewer unmoved. Carter's casual arrangement works beautifully here, where we feel the high spirits and warmth including us too. I think that it's partially the scale of the pictures and the fact that we have to approach them closely—as if we were indeed perusing a scrapbook—that makes it feel so inclusive. I reacted to these not as to pictures of strangers, but as to people whose happiness I shared. I felt no barrier. The viewer is one of the company, and happy to be be there as a familiar of these people.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. Collection of friendship photographs. |

Are we reading an autobiography or are we a character in the artist's? Are we following a tale of Everyman? The question cannot help but come to mind at many points, but especially as the narrative descends from confident, social well-being to a chapter of literal effacement—a Slough of Despond if you will.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

The narrative continues through several more chapters that alternate roughly between presence and absence, between happily socialized security and images of vacant, drifting society.

A chapter focused on the photographer herself is particularly arresting. It would be poignant were the pictures not so bold and frank. As usual, many pictures—large and small—are assembled, but the viewer has to think twice to grasp that the subject is the artist, so they must have been staged. Every one of them has the air of complete spontaneity: funny faces, dramatic poses, but of artistic quality far beyond the photo booth. They are so natural, in fact, that they raise doubts about everything that has come before. Maybe the show really has been the work of an anonymous third party.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

The cluster of self-portraits focus on large, matter of fact images in full color and in sepia, of the artist in the hospital, recovering from abdominal surgery. The brilliantly-well lit hospital room with the bloody tubing emanating from her belly is unnerving except that she faces the camera as if she were in conversation with you, the friend close enough to be visiting. Throughout the show, you have been reeled into her world and point of view and now, here you are, paying a post-op visit, the kind you wouldn't be able to stomach with any but your very best friend.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

I'm not sure that Carter is acquainted with John Bunyon's The Pilgrim's Progress, but in this show I feel a connection with that tale of moral trial and resilience. The artist takes us through eight passages of pleasure, doubt, and grief. Without denying beauty, she doesn't stop to lament when it's absent. A calm, even-handed air of acceptance runs throughout the show, whether we witness happy camaraderie or pictures of lost of identity.

I think Maika Carter's first solo show is a knock-out. She shows her powers as a photographer, as a story-teller with an excellent editorial sense, and as an individual with the wisdom and intuition that make her skills important. I, for one, will be following with great interest an artist who shows such maturity straight out of the box.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call It Something or Call It Nothing. |

.jpg)